An interview with art historian Ksenia M. Soboleva discussing lesbian invisibility, being a grumpy dyke, and the value of criticism.

By Sara Duell

Would you describe a bit of your background and how you ended up in New York?

I was born in Moscow, but I mainly grew up in Arkhangelsk, Northern Russia—I lived with my great-grandmother. When I was eight my mother and I moved to the Netherlands, and that’s where I came of age. I studied art history at Utrecht University for my undergrad, but I didn’t find it to be very rigorous or exciting, so at the time I had no intention to pursue grad school. It was only when I visited Madrid in 2012 and saw the Sharon Hayes exhibition Habla (curated by the brilliant Lynne Cooke) at the contemporary art museum Museo Reina Sofía that I realized what art and exhibition making could be. I didn’t really learn that much about queer history or queer artists during my undergrad, so I would say it was really this exhibition that made want to pursue grad school. But I knew that I didn’t want to stay in the Netherlands, and I had this dream of moving to New York to study with Linda Nochlin, who wrote the famous essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”, so I applied to the Institute of Fine arts, NYU. I got in, came to New York, but unfortunately Nochlin retired a year later. I was fortunate enough to see her lecture, but sadly never got the opportunity to take a class with her. But anyway, that’s how I ended up in New York; I loved it, so I stayed and pursued my PhD.

I’m assuming your interest in lesbian artist started well before grad school.

The interest definitely existed, but I was a huge closet case until well into college. Funny story; when I was six years old, I took drawing and painting classes at an art gallery in Arkhangelsk, of which my aunt was the director at the time, and I had a huge crush on my art teacher, who kind of looked like Liza Minneli in Cabaret, with short black hair and bright green eye shadow. It’s such a cliché, but I just adored her. The way I decided to make sense of it at that time, was to conclude that the passionate feelings I was having were not for the art teacher, but for art itself. So if I hadn’t been a lesbian, I might not have become an art historian. But I only started seriously studying queer art and culture in grad school.

“So if I hadn’t been a lesbian, I might not have become an art historian.”

How did you end up focusing on lesbian artists and the AIDS crisis in New York for your dissertation?

The AIDS crisis in an art historical context only entered my consciousness when I visited the 54th Venice Biennial in 2011 (this was during my undergrad). The Norwegian pavilion that year was taken over by the artist Bjarne Melgaard, whose project Baton Sinister centered on the stigma around HIV and AIDS. One of the pieces was this poster that said “Don’t get fucked up the ass. Period.” It addressed the government homophobia and what the solution to AIDS was according to the government, basically: don’t be gay and you won’t get AIDS. I was really captured by the project, I guess because I hadn’t really been confronted with AIDS in an art context, and especially not in a language context before, and it really resonated with me.

At the time, I didn’t think twice about the fact that the project presented HIV/AIDS as a gay male issue. It wasn’t until I moved to New York, when I was doing preliminary research on lesbian artists of that generation, that I kept encountering references to the AIDS crisis in their biographies, in catalogue essays on their work; they were all crucially informed by the AIDS epidemic. But then when I would read art historical scholarship on art of the AIDS crisis, the lesbian was almost entirely absent. Even the most recent large survey exhibition on art and AIDS: Art AIDS America (Tacoma Art Museum in partnership with The Bronx Museum of the Arts’) barely mentioned lesbian artists, and only included a few women artists. I thought that was strange and that’s how I first started thinking about it. The first conference paper I ever gave was about the lesbian activist art collective fierce pussy, and their role during the AIDS crisis.

I was very drawn to the sense of community queer people who lived through the AIDS crisis all seemed to have felt, and that was something I personally had not experienced in my life. My dissertation is driven by a profound admiration for that community; doing research on it was a way to getting closer, and also making sense of my own identity.

What are some interesting takeaways from your research?

It’s been a challenge to study a history of visual culture that is so rooted in invisibly. You can’t underestimate the extent to which lesbian contributions just tend to magically disappear both from feminist discourse and from queer discourse. Lesbian invisibly is no joke. There is a lot of contemporary stuff happening on lesbian visual culture which I think is wonderful: Instagram accounts dedicated to lesbian culture, TV shows, films. I think Portrait of a Lady on Fire is the first truthful depiction of the lesbian gaze. But if popular culture doesn’t somehow bleed into academic scholarship, then there is still a real lack. Especially in the field of art history, there are surprisingly few serious considerations of art and lesbian identity. Lesbians also haven’t held the same amount of tenure track positions in academia, or prominent museum-jobs, as gay men. It’s not only lesbian artists who haven’t received enough career opportunities throughout history, but also the lesbian historians who are most likely to write on them. Whereas gay men have always had a network, a support system. Historically, the art world was one of the few spheres in which gay men could get prominent positions. It wasn’t the same for lesbians. When Harmony Hammond organized “The Lesbian Show” in 1978, many lesbians declined the invite to participate, because it was still dangerous to come out and it could really hurt your career. One lesbian artist was even threatened by her gay male gallerist that he would drop her from the gallery if she participated in the show. Harmony Hammond’s Lesbian Art In America is a great source for lesbian art history, by the way. She was really one of the pioneers for creating a context for lesbian art.

Which historians do you look up to?

My go to is Catherine Lord, who is just a brilliant writer, curator, and artist. She has written a ton about art and lesbian invisibility; there’s an essay on Louise Fishman’s Angry Paintings that I could probably quote from memory. Then there is Terry Castle, who is an English Professor at Stanford. She wrote The Apparitional Lesbian: Female Homosexuality and Modern Culture (1993), which was a great starting point for my research. Ann Cvetkovich has made an invaluable contribution with An Archive of Feelings, which explores lesbian trauma and has an entire chapter on ACT UP’s lesbians. Elisabeth Lebovici, who’s in Paris, recently wrote a great book on how AIDS affected her life, with a particular emphasis on lesbian artists as well. She maintains this very personal voice throughout her scholarship which I really admire. Also, Helen Molesworth is a big inspiration in terms of curating, and also a wonderful writer; the exhibition catalogue of This Will Have Been is a staple on my desk. My scholarship is also very informed by queer theory; I love Sara Ahmed and Heather Love’s work.Last but not least, there’s Jan Zita Grover and Laura Cottingham, who don’t write on art and lesbian identity anymore, but were powerful voices in the late 1980s and early 1990s. I actually dedicate an entire chapter of my dissertation to the disappearing lesbian, or the lesbian who drops out. So many people who were actively writing about lesbian visual culture during the AIDS crisis just sort of seem to have dropped out.

Why do you think that they dropped out?

It has a lot to do with trauma, as Ann Cvetkovich argues as well. I also think that they didn’t receive the recognition they deserved, and when that period of the AIDS crisis started to be historicized, lesbian contributions were excluded. Even though it was the lesbian sex wars that informed much of the theory during the AIDS crisis. Cindy Patton was crucial to Douglas Crimp’s scholarship, for example, which he acknowledges. A lot of queer theory emerged out of AIDS activism, and AIDS was informed by lesbian writings of the sex wars. Lesbians brought so much to AIDS activism, because they had already become politicized during women’s liberation and then the sex wars. They knew how to organize. I’m certainly not the first to point this out, but people tend to forget, overlook, or just not care about the lesbian contributions. Everybody knows who Douglas Crimp is. How many people remember Cindy Patton? I’d be interested to know.

Anyway, I can’t reach Jan Zita Grover, I think she opened a puppy rescue and wrote a children’s book about dogs. I also heard she was teaching cooking class somewhere. I have no idea where Laura Cottingham is, last I heard she was traveling through Egypt. But what’s sort of comforting is that other queer scholars of my generation seem to have the same issue. In Spring 2019, I organized this symposium, Queering Art History, which is how I met a lot of other young queer scholars working on similar stuff. After the symposium we went out for drinks and as we were chatting we realized that we all were running into the same issues with the same people, like: “this person won’t talk to me”, or “I can’t figure out where this person is,” or “this person emailed back but they seemed kind of rude.” It was hilarious, and a good reminder that we shouldn’t take things personally.

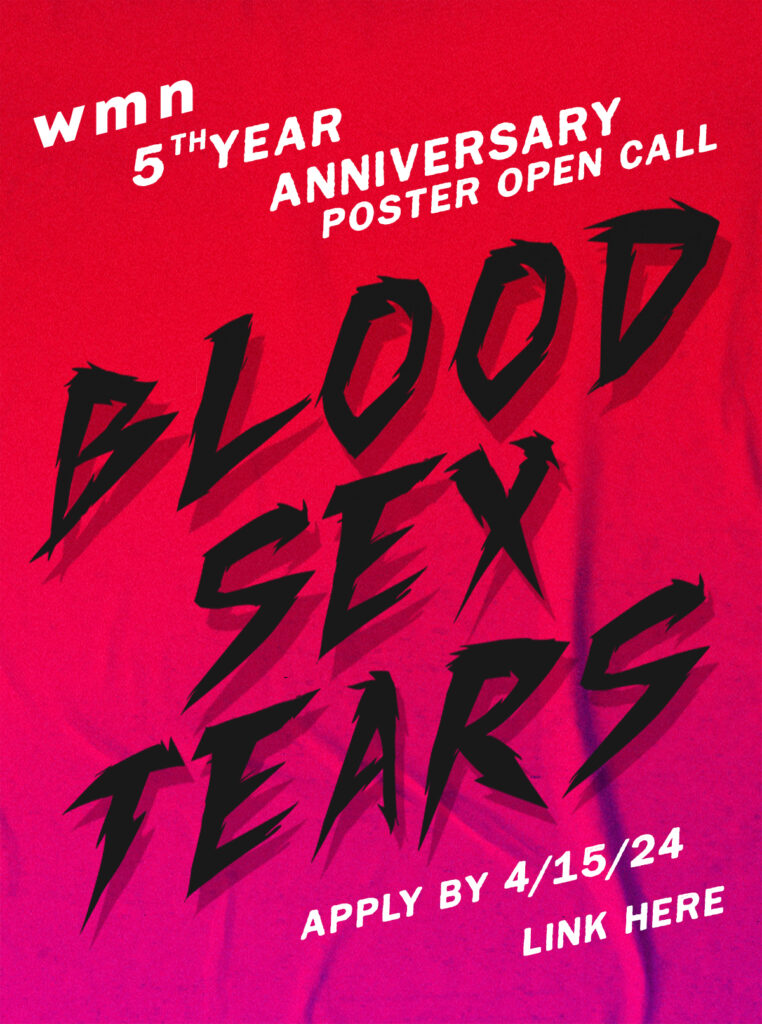

And even though you might encounter more gay and queer art today than before, I find that it’s harder to just come by lesbian art, which was one of the reasons I started WMN with Jeanette and Florencia because I realized I knew very little about lesbian art and history. I’ve learned a lot over the last year, but it takes a lot of research even just for something as simple as posting on Instagram.

To me that’s the beautiful thing about being queer. Coming out tends to incite this passion for research, for a lot of queer people at least, it is the way we make sense of ourselves. Most of us don’t have queer parents, or any queer family members, but queer ancestry extends beyond familial and biological relationships. So we go to the library, or I guess today you can look under the queer category on Netflix. We look at history to show us proof of our existence, that others like us existed before we came along.

“We look at history to show us proof of our existence, that others like us existed before we came along.”

What does the word lesbian mean to you?

So many things. I think it’s a common misconception that lesbian is a fixed identity, while queer is so fluid. I think that the term changes over time, it means different things to different people in different places. It’s funny, when I tell people in New York I’m a lesbian it comes across like I’m using this super outdated term and am like a 75 year old lesbian separatist or something. When I tell people in Russia I’m a lesbian, it’s super shocking and radical and just like “whoa she said the L word out loud.” The reason I insist on the meaningfulness of the term lesbian is because of the history that it carries, a history that hasn’t been sufficiently documented. Studying the ways in which lesbian identity has shifted over time is absolutely crucial to the history of queer identity. Lesbian and queer aren’t mutually exclusive, it’s not an either or. A lot of people assume that if you identify as a lesbian you must have some problem with the term queer or you must be essentialist, which is not at all the case. I hope that my own scholarship shows how lesbian can exist alongside queer, and how the two contribute to one and another, how they can strengthen each other, and how both have flaws and challenges.

“The reason I insist on the meaningfulness of the term lesbian is because of the history that it carries, a history that hasn’t been sufficiently documented. Studying the ways in which lesbian identity has shifted over time is absolutely crucial to the history of queer identity. Lesbian and queer aren’t mutually exclusive, it’s not an either or.”

Another fun fact, thanks to Terry Castle. The first time the word queer was used in a gender sexuality context, it was used as a code word for cunt, by Anne Lister in her coded diaries from the 19th century. So queer has this inherently lesbian origin, yet it has somehow swallowed up the lesbian. I’m constantly asked why I identity as a lesbian instead of a queer woman, and none of my gay male friends seem to get the question why they identify as gay instead of queer. The lesbian is such an awkward term to many people, which is sort of what I love about it. You know, my yoga teacher always says something like “the way we become comfortable in uncomfortable positions, is if we stay in them.” I like meditating on the awkwardness of lesbian.

Which makes me think of your article about artist and AIDS activist Tessa Boffin in Hyperallergic, where you mention how scholars who started writing about gay history intentionally focused on the fun parts, but how important it is to also to highlight the darker aspects of LGBTQ history.

Yes, and I should mention that it’s Heather Love’s book Feeling Backwards that truly shaped my approach to this. People tend to act like we always got along, and were one big happy family. And sure, on one hand there has always been a strong sense of community to some extent. But queer history is full of exclusions and frictions. It’s valuable to study those messy histories just as closely as the histories of pride and victory.

What are your thoughts on lesbian visibility currently and for the future?

I co-chaired a panel The Return of the Lesbian? Examining Lesbian Visibility in Art History’s Present, Past, and Future at the art history conference CAA with my friend Alexis Bard Johnson, who is the curator of the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries in Los Angeles. The panel explored the recent re-emergence of lesbian visual culture in the form of Instagram accounts, TV shows, etc.. but at the same time an increasing reluctance for people to identify as lesbian. The panel tried to make sense of these opposing trends. But what we concluded at the end of the panel is that there cannot really be a return of the lesbian if the lesbian has never been turned to. That’s what I’m trying to say when I talk about popular culture versus academic scholarship, it’s not that I’m discounting the former, in fact my work is very much informed by it, but I think that in order to properly turn to the lesbian we need to create a solid, rigorous discourse on the history of lesbian identity, which is on its way but we’re not there yet. Laura Cottingham said: “Without any sense of our historical place, how are we to understand or produce our meaning in the present?” I’m very happy that there are groups like you [WMN zine] who keep insisting on the meaningfulness of the lesbian. I was also so moved by Barbara Hammer’s last interview before she passed away, with Masha Gessen in the New Yorker, where she said “we don’t want to forget the lesbian, and we don’t want her to be lost”. Thank you, Barbara.

You’ve described yourself as a grumpy dyke, but no wonder you’re grumpy if you’re continuously having to try to work against a field that is ignored and people that don’t respond.

You know, I should clarify that I don’t mean this as a complaint. I like being a grumpy dyke! I like disagreeing with people, I like being at odds with a lot of contemporary writing on queer art. I think there is a tendency within the queer community to be overtly praiseful, which I understand because of course we want to support each other, but I also think that in order to create a rigorous discourse, art criticism should make no apologies for itself. We should disagree, argue, hold each other accountable. As long as we don’t drag each other down. Catharine Lord once told me that criticism is a form of generosity, and I couldn’t agree more. To sit down and think about somebody’s work, whether you’re critical of it or not, is a form of praise in itself.

Which is funny working within an American context. I think it’s pretty unamerican to disagree.

Totally, I remember my first graduate seminar, I raised my hand and said something along the lines of “I disagree because…” and then later a classmate told me that in America first you say ‘I really like the point you made about X, and I really appreciated your careful consideration of Y, however I just wonder if in this particular very specific respect you could have perhaps potentially elaborated a little bit on…” That’s another thing I had to learn when I moved here.

Also, when I first started writing about lesbian artists of the AIDS crisis, I remember emphasizing that gay men had come to define the period and there was very little art historical scholarship on lesbians simply because there was this misguided notion that they weren’t affected by AIDS just because female-to-female transmission was rare (but not impossible, and some lesbians have sex with men, or were intravenous drug users). The AIDS crisis affected the entire queer community; it was more than a medical crisis, it was a socio-political crisis. People were dying because of government neglect, because of homophobia. Lesbians weren’t allowed to donate blood because the entire queer community was considered to be dirty, basically. AIDS was viewed as symptom of being queer. But anyway, I was pushing so hard for the consideration of how the AIDS crisis affected lesbian artists, that at some point I read over my proposal and I was like: Oh my god. It sounds like I hate gay men, and don’t think their art deserves the attention it has received—which couldn’t be farther from the truth. Needless to say, I completely rewrote it. I’m by no means discounting their work. I just want to bring in the lesbian voices too.

Ksenia M. Soboleva is a Russian-Tatar writer, art historian, and curator based in Brooklyn. Currently, she is completing her PhD at the Institute of Fine Arts, NYU. Soboleva’s dissertation focuses on lesbian artists and the AIDS crisis in the United States (1981-1996), framing it within a larger genealogy of lesbian (in)visibility. Previously, Soboleva has curated exhibitions at the 80WSE Project Space, Assembly Room, Honey’s, SPRING/BREAK Art Show, and Stellar Projects. She has taught at NYU and the Cooper Union, and presented her research at various institutions in the United States and abroad. Her writings have appeared in Hyperallergic, The Brooklyn Rail, art-agenda,and QED: A Journal in LGBTQ Worldmaking, among other publications. Most recently, she launched a virtual series of artist talks in collaboration with The Center in New York, to highlight lesbian and dyke visibility. Soboleva is the 2020-2021 Marica and Jan Vilcek curatorial fellow at the Solomon R. Guggenheim museum in New York.